Lace

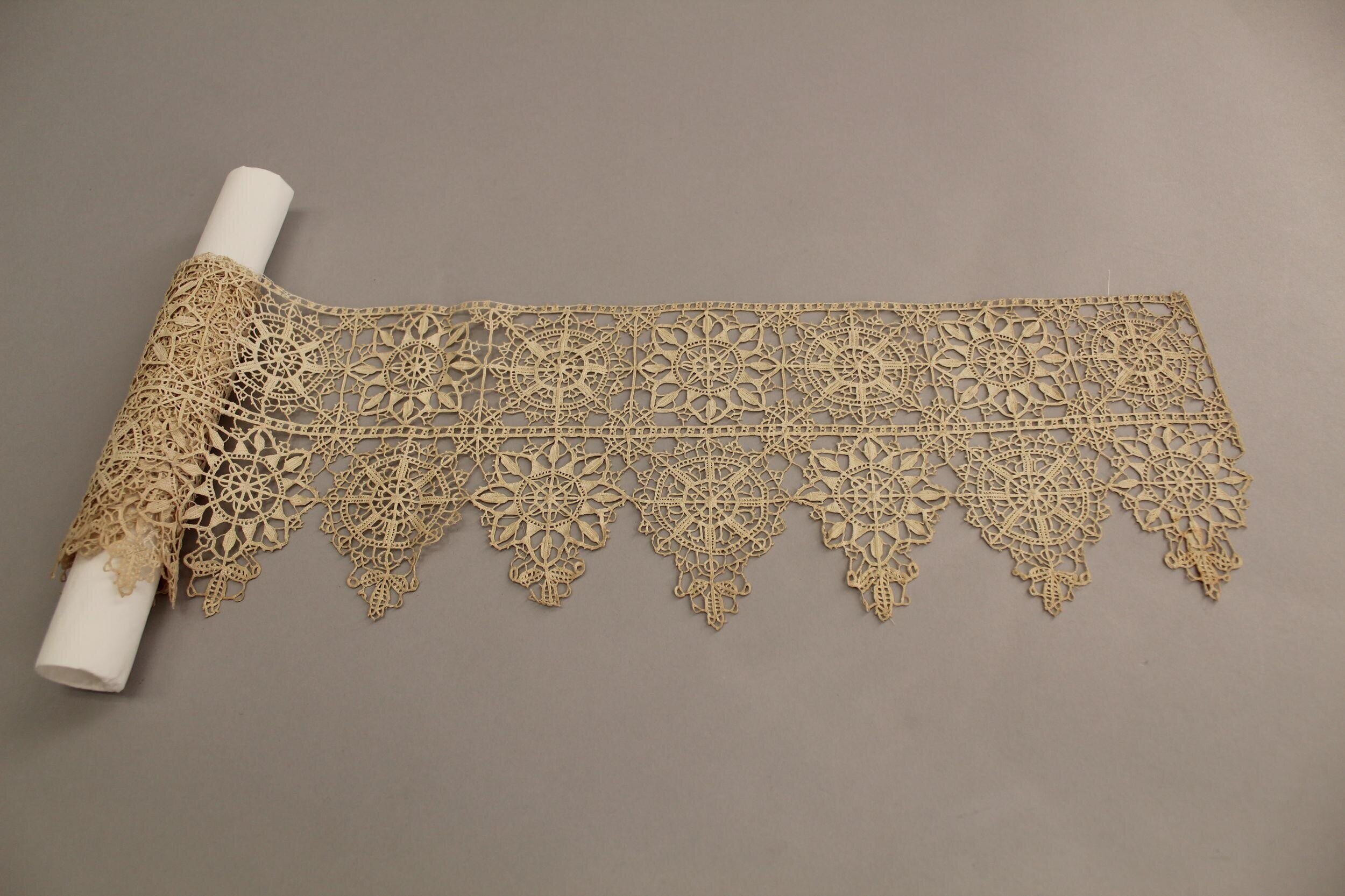

I would like to examine here a decorative clothing element that is not included in Titian's portrait of Isabella d'Este: lace. I draw the reader's attention, however, to the ruffle of fine linen that is found at the collar and cuffs of Isabella's blouse that is embroidered in blackwork. Lace developed in Italy in the fifteenth century, firstly as drawn or cutwork of such elements of linen clothing. The threads of the weave would be pulled out, or cut away, with the ensuing gap neatened with decorative needlework and embroidered lace to form a border (Fig. 1, right). To the edging of such cuffs and collars would be attached further needlework lace, resulting in a trim of fine lace. A most extreme form of embroidered lace cutwork is reticella, first referred to in a 1493 Sforza inventory, in which geometric patterns are built up on a grid in the form of a net (hence the name meaning "small net"), as shown in figures 2 and 3 (right), and in Frans Pourbus the Younger’s circa 1602-03 Portrait of Empress Eleonora Gonzaga (Fig. 4, below).

Reticella (otherwise known as point coupé) developed into an even more elaborate form of needlelace called punto in aria, in which no ground material is used for the making of the lace, which is "stitched in the air". In reality, a linen and parchment base with a drawn pattern was used upon which the needlework lace was stitched. When completed the parchment backing was peeled off leaving the lace product, with no support. Punto in aria was employed in the production of collar and cuffs trims, especially the elaborate ruffs that became fashionable in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. A beautiful example of a punto in aria ruff can be found in Frans Pourbus the Younger's circa 1615 portrait of Elisabeth of France, Queen of Spain, now in the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid and available in high resolution here.

Fig. 4 Frans Pourbus the Younger, ca. 1602-03. Portrait of Empress Eleonora Gonzaga. Oil on canvas, 64 x 49 cm. Florence, Palazzo Pitti © Gallerie degli Uffizi, su concessione del Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali e per il turismo.

By the middle of the seventeenth century, lace had become a staple in court dress, especially in France. The dresses all contained some form of lace decoration around the collar and cuffs of the sleeves, or even on the bodices. As Medici Resident and agent in Paris, Abbot Filippo Marucelli explained in April 1665, lace was indispensable if one was to follow the latest trends in French fashion, referring to the “many pieces of laces of considerable value, without which one cannot express the fashion in a certain manner." As to this type of decoration, we can cite the opinion of Mademoiselle de Guise, Marie de Lorraine, who informed Marucelli's secretary, Paolo dell'Ara, that the fashion in Paris in the mid 1660s was for some (but not too much) lace trim on the bodice and sleeves of the French princesses’ dresses. By the late seventeenth century these dresses had developed into full lace outfits, as we shall see.

Lace was, in fact, the luxury commodity that elite women throughout Europe most coveted, and a marker of social distinction and wealth. Only the most wealthy could afford lace, as it was amongst the most expensive textiles, due to its specialised technique, worked by expert women who laboured many hours in its production. Thus it became one of the most collectable textiles amongst the elite, and items made of lace — handkerchiefs, cuffs, collars, lapets, petticoats, caps and veils — were the most frequently gifted presents amongst European court ladies, a gendered practice that saw women at the heart of production and consumption, and the mediators of taste and cultural transfers throughout the Continent.

For example, Vittoria della Rovere, Grand Duchess of Tuscany (and a descendant of Isabella d'Este on her father's side), would source her lace both locally, from nuns in Florentine convents — it was, in fact, the luxury textile she most sought from the nuns — but also from Venice, through her agent, Paolo della Sera, as well as from Bologna and Genoa, and from France in the 1660s, when Parisian court styles became the height of European fashion. She even had her own ladies-in-waiting taught this most precious skill by local nuns, as in the case of Maria Maddalena Caligari, or by sending them to Paris, as she did with Caterina Angiola Pieroncini, to learn the latest techniques and styles (Point-de-France) under the guidance of a French Maestra, Mademoiselle Alée. Vittoria, moreover, would often gift lace to her friends in France who sent her regular consignments of clothing, in appreciation and as a means of strengthening their affective and socio-diplomatic ties.

In Italy, not only did local nuns produce this prized luxury textile, they taught young girls in the convents this most specialised skill, who then went to work in important centres throughout Italy such as Venice, Milan and Genoa. Each city developed its own specific style and type of lace for which they were renowned. Lace from Italy, especially Venetian Gros-point needlelace (Fig. 5), was considered the most beautiful, and initially the most highly-prized throughout Europe. By the second half of the seventeenth century lacemaking had also become one of France’s most profitable industries. The preference of Louis XIV’s court designers and tailors, initially attracted to the heavier, sculptural Venetian Gros-point needlework lace, as seen in Lefebvre's portrait of Colbert or Bernini's sculpted portrait of the king, soon sought the finer and more softly falling bobbin laces such as that produced in Flanders and Brussels to fashion into cravats, cuffs and handkerchiefs. Flemish and Belgian bobbin lace had also been favoured at the English Caroline court by Queen Henrietta Maria de Bourbon of France, Maria de’ Medici’s daughter and consort of Charles I, as seen in many portraits by court artist Anton Van Dyck.

Fig. 5 Cuff (one of a pair), 17th century. Needle lace, gros point lace, 59.7 x 20.3 cm. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 30.135.153a.

Henrietta Maria would send gifts of Brussels lace to her family and female friends in Paris, such as Queen Anne of Austria, her brother, Louis XIII’s wife, thereby influencing French fashions. This was referred to as Point d’Angleterre (‘English point’), because in order to protect local industry, production bans had been put in place from the early 1660s both in England and France against the importation of Belgian and Flemish laces. It was believed that local lace makers with their inferior heavier flax could not compare with the high quality of the important product. In France, where the Minister Colbert wished to compete with foreign production, lacemaking centres were established, such as that at Alençon, with the Minister paying Venetian and Flemish lace-makers to migrate and settle in these regions in order to instruct the local women in their famed needlepoint and bobbin lace techniques. The local product came to be known as Point-de-France (French point). Lace produced in England, however, was permitted, so merchants found a way around the 1665 Royal Proclamation by calling all their imported laces ‘English point’. Indeed by the 1670s, Point d’Angleterre — the term used generically to refer to high quality Belgian bobbin lace, whether produced in Brussels or Devon, such as Honiton lace — had become the height of elite French and European fashion, a ‘must have’ with all the court ladies, from Madame Scuderie to Madame Sevigny. This can be seen in a 1678 print that appeared in the Parisian magazine the Mercure Galant, showing a French noblewoman’s summer manteau dress designed by Jean Le Pautre. Every lace element of the outfit, from the cuffs of the double sleeves, dress skirt, and underskirt, is produced in Point d’Angleterre.

Fig. 6 Pattern design for reticella lace, Elisabetta Catanea Parasole, Teatro delle nobili e virtuose donne, Rome 1616, p. 7. Image: https://www2.cs.arizona.edu/patterns/weaving/books/pe3_lace_1.pdf

The sources of the lace designs themselves were usually male-authored pattern-books, such as Cesare Vecellio's Corona delle nobili e virtuose donne (Venice 1617); the Venetian Federico Vinciolo's Les Singuliers et Nouveaux Pourtraicts, published in Paris in 1606; or Vari disegni di merletti inventati da Bartolomeo Danieli bolognese (Bologna 1636). There was, however, one woman lace designer, Elisabetta (or Isabella) Catanea Parasole (c. 1575 - c. 1625) from Rome, who published her own wood engravings of lace patterns (as well as embroidery designs), in a series of pattern-books at the turn of the seventeenth century, dedicating them to such illustrious women patrons as the aforementioned Elisabeth of France (Queen consort of Philip IV of Spain) and Donna Juana de Aragona and Cardona. These included the Teatro delle Nobili e Virtuose donne: dove si rappresentano varii disegni di lavori; nuovamenti inventati et disegnati da Elisabetta Catanea Parasole, first published in Rome in 1616, and which was extremely popular, with multiple editions appearing right up to 1636. Parasole's texts are unique in that they celebrate female creative invention and ingenuity, considered at the time to be only male artistic attributes, and are the only extant pattern-books produced for women by a female textile designer. Comparing the patterns from such design books (Fig. 6) with extant examples of early modern lace, and the period's portraits of sitters wearing lace collars and ruffs, one can see how closely the manufactured lace items compared with the published designs, and that these patterns were highly relied upon as sources. Such pattern-books were not limited to Italy or France, but also appeared throughout the Continent and British Isles, indicating a widespread production and circulation of this highly prized textile art.

Adelina Modesti, University of Melbourne

Select bibliography

Textile Research Centre, Leiden. “Reticella”. Last modified 5 March, 2017. https://trc-leiden.nl/trc-needles/techniques/lace-making/reticella.

—— . “Punto in Aria“. Last modified 3 January, 2017. https://trc-leiden.nl/trc-needles/regional-traditions/europe-and-north-america/lace-types/punto-in-aria.

Browne, Clare. Lace from the Victoria and Albert Museum. London: V & A Publications, 2004.

Crowston, Clare Haru. Fabricating Women. The Seamstresses of Old Regime France, 1675-1791. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001.

Earnshaw, Pat. A Dictionary of Lace. New York: Dover, 1999.

Levy, Santina M. Lace. A History. London: Maney, 1983.

Modesti, Adelina. "Nun Artisans, Needlecraft, and Material Culture in the Early Modern Florentine Convent". In Artiste nel chiostro. Produzione artistica nei monasteri femminili in età moderna, edited by Sheila Barker and Luciano Cinelli, 53-71. Special issue of Memorie Domenicane, n. 46. Florence: Nerbini 2015.

—— “‘Nelle mode le più novelle'. The latest fashion trends (textiles, clothing and luxury fabrics) at the court of Grand Duchess Vittoria della Rovere of Tuscany". In Telling Objects. Contextualizing the role of the consort in early modern Europe, edited by Jill Bepler and Svante Norrhem, 107-29. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2018.

—— Women's Patronage and Gendered Cultural Networks in Early Modern Europe: Vittoria della Rovere, Grand Duchess of Tuscany. London and New York: Routledge, 2019.

Jessica O’Leary